- Home

- Alex Morgan

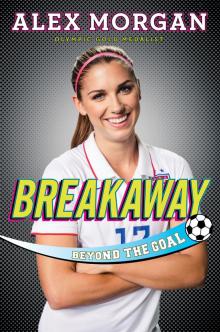

Breakaway

Breakaway Read online

To my parents, Pam and Mike;

my mother-in-law, Gloria;

and my husband, Servando,

for their advice and guidance

Preface

* * *

Something wasn’t right. Actually, something was really wrong. The pain in my right knee was sharp, and it wouldn’t stop.

A minute ago I’d been a normal seventeen-year old, with a position on a national soccer team and an athletic scholarship to one of the best colleges in the country, and now I was lying on the field clutching my knee as if that would make the pain go away.

“Help! Something’s not right. I’m hurt,” I whimpered to the boy who was kneeling next to me. “I think I need some help.”

Maybe I should have been angry at him, but I was too worried about my knee. I knew he hadn’t meant to injure me. I’d been chasing him down, and when I’d reached him, I’d tried to block his kick. But he’d faked and cut the ball to avoid me. I’d tried to cut him in return, but my body had gone right and my knee had gone left. I’d felt immediate pain, and as emotions flooded over me, I’d realized within a millisecond that I couldn’t walk. Something was very, very wrong.

I tried to focus on something, anything, to take my mind away from the pain. Think positive thoughts, Alex. It’s a beautiful day in Southern California. You’ve just received a soccer scholarship to Cal, and you’re playing on a national team. Everything’s coming together, and you’re going to be okay.

My team had been scrimmaging with the men’s junior national soccer team when I fell. It was fun, not too serious, but a good way for me to develop as a player and challenge myself. I’d always liked training with boys. Maybe it was because I have two sisters, so being around boys was sort of exciting and different.

My dad had always been my biggest supporter, and in fact, he was at practice that day watching me. While I couldn’t see him, I assumed he was rushing toward the field to find out what was going on. Despite my pain, I smiled at the thought of him. He always encouraged me, and some of my fondest memories were of practicing with him.

“Corners, corners, shoot for the corners!” he would say. “Head down, follow the ball into the net.”

Oh, Dad, I thought. Did he really think I didn’t know the basics of soccer when I was sixteen years old? I owed so much to him. He’d gone to all my games, and we practiced together at least twice a week. Sometimes four or five times. We would go across the street to the middle school. If that field was occupied, we would go to Pantera Park. If people were on that field, we’d go to Peterson Park. He never gave up.

I couldn’t let him down. He wouldn’t get mad if I moved on to something else—he never pressured me about soccer, or anything, really—but I knew I was poised for something great, and I wanted him and Mom to be proud of me. I wanted to play for Cal; I wanted to feel an Olympic gold medal around my neck; and I wanted to win the World Cup. I had goals, and I was determined to meet them.

But first I had to stand up, get off the field, and figure out what was wrong with my knee.

Note to the Reader

* * *

I have always set goals for myself. Even when I was little, I had hopes—big and small—about everything. They mostly centered on soccer, but to me soccer is life. It’s not just a game; it’s a way of thinking, dreaming, and being. But you don’t have to be a soccer player to have wishes and hopes. You can have objectives no matter what you do. And if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s that you don’t have to meet your goals on your first try, or even your tenth. Setting targets and working toward them is what counts. And it’s so important never to forget that.

When I was lying on that soccer field, so many thoughts were running through my seventeen-year-old head, but most of them centered on the goals I’d set for myself. I’ll talk more about that awful afternoon and what happened in the days and weeks after it, but thinking back on that day, I wish I’d realized that a setback doesn’t mean you won’t reach your goals someday. I’ve had so many big bumps in the road in my life, but they’ve all taught me something. They’ve shown me how to accept challenges, work hard to overcome them, and in the end, forge a path toward my true purpose.

I hope this book helps you discover the many ways that you can go after your dreams. I’m so young that my life is really just beginning, and yours probably is too. But being on the soccer field has taught me some really important lessons, specifically about setting goals and embracing your passions. I’ve learned that life can be wonderful if you have the right attitude, work hard, and dream big, and my wish is that reading this will help you set the objectives that will make each day richer and fuller than the last.

—Alex

CHAPTER 1

* * *

I was doing things my own way even before I was born. After having two girls, my parents wanted a boy. Not that having a third girl is a bad thing; they just wanted something different. But I had my own set of plans, and when I was born on July 2, 1989, there I was: a little baby girl.

With each child my parents had had an agreement. If they had a boy, my dad would choose the name, and if they had a girl, my mom would have the honor. My mom settled on the name Alexandra for me. I can only guess that’s because my dad had chosen the “boy name” Alexander, and my mom decided to allow him just the smallest bit of influence.

What’s so funny is that even though my dad doted on his girls, he had a real vision of how he would have raised his son, if he’d had one. He once said that since I was the third girl, “he was going to make a boy out of me somehow.” He was joking, of course—he loves having three girls and wouldn’t trade us for anything—but I think he had certain hopes as a father. My dad grew up playing baseball, and he dreamed of a son playing it, living out what he’d loved most as a little boy.

I’m getting ahead of myself, though. Way before my dad helped introduce me to athletics, I was just a little kid growing up in Diamond Bar, California, about twenty-five miles east of Los Angeles. Diamond Bar is a nice suburban community—quiet, sunny, and generally happy. I liked it there. Mostly everyone knew one another, and I was able to walk to elementary and middle school.

But there wasn’t very much going on in Diamond Bar. It was a huge deal when we got a Target, and we didn’t even have a chain restaurant until I was fifteen or so. It’s the kind of place that you’re happy to grow up in but also happy to get out of once you come of age. I think so much of my youth revolved around sports precisely because not much else happened around me.

My parents basically grew up together. My dad was best friends with my mom’s older brother, and he’s as close with my mom’s siblings as she is. In fact, he probably sees them even more than she does! My parents starting dating on and off when my mom was eighteen or so, and they got married and had my eldest sister when she was twenty-three and he was thirty-four.

My dad owned and ran a small construction company, and my mom worked with him until she decided to get her master’s degree when I was about six. My two older sisters, Jenny and Jeri, were my best friends. Jenny is six years older than me, and Jeri is four years older. I was very close to Jeri, experiencing intense ups and downs like you do with your friends, and Jenny was a little more of a mother figure to me, especially when my mom went back to school at night. She happily dove into a caretaking role and began cooking for the family and organizing things for us while our mom was at class.

I was always in their shadow. When you’re the third kid, it’s just like that. You’re considered “the baby.” And my mom always got us confused! When she’d call me for something, she’d say, “Jenny! Jeri! I mean Alex!” She definitely valued us as individuals, but three girls can be a whirlwind!

My parents were stricter with me than they were with my sisters. Even though I was kind of sweet and shy and not at all a troublemaker, they held me to a higher standard. Maybe they knew my potential, or maybe they wanted to do everything right for their last child.

I remember we used to play so many games. Family games on Wednesday nights were always a big deal, especially with my dad. We’d play gin rummy or Monopoly or other board games, and they were really competitive. That’s where I got my fighting spirit; competition was a positive thing in our house, not a negative one. There were always winners and losers, though—nobody would be handed a win out of pity. My mom was actually the only one who wouldn’t laugh in your face when she won. If it was just me and her, the outcome of the game really didn’t matter. But not my dad! He would literally do a dance around the house after he won. It was extremely annoying.

Like I said, competition was all in good fun, but I’m not sure how fun Jeri thought it was when I first beat her in a footrace. I’d always been one step behind her in everything, but when I was nine I realized I was pretty fast and I might have a chance at doing something better than her. I’d stopped thinking my name was “Jeri’s little sister” instead of Alex, and I was going to assert myself!

“I’m going to beat you! You’ve got no chance. I’m going to win,” Jeri yelled at me as we were about to race against each other at the school across from our house.

“Just you watch me,” I said as I took off running.

Jeri couldn’t even keep up—I crossed the finish line way before her. I’m sure she’d deny it to this day, but I remember it clearly. I totally killed her.

My dad really wanted us to be athletic, and we all played different sports when we were little. I played soccer, softball, basketball, volleyball, and even participated in local track meets, which I loved.

I was probably three when I really learned how to catch a ball, and that was when Dad decided I was destined for softball. My sisters had been playing in a softball league for years, so I’d seen lots of their games. I remember holding on to the fence outside one of their games, poking my nose through as I cheered them on. Dad signed me up for a team as soon as I was old enough, and from then on I played softball more often and more intensely than any other sport. The first team I played on was a T-ball team called the A’s, and it was, of course, coached by my dad.

Jenny and Jeri were really good at school, but I took to athletics a little more than them, so I think that’s when my dad started pushing me harder than them. It wasn’t in a bad way—he just nudged me to do something I seemed naturally inclined toward and that I liked.

We would go to Anaheim Angels baseball games all the time. My dad had season tickets for a few years, and every time we went, he made sure that I brought my glove just in case I caught a foul ball. It was always so fun going to games, but now that I’m so into soccer, I look back and think, Wow, baseball is boring. Why did I enjoy it so much? Maybe it was just because I liked making my dad proud.

One day when I was about nine, though, I decided I’d had enough. I’d been playing soccer since I was five, and I’d realized that it was the sport for me.

I turned to my dad and said, “You know what? I don’t like softball.”

“What?” I could see the shocked look on my dad’s face. I was so good! How was it possible that I didn’t like it?

“I like soccer. I like to run.”

Dad’s face visibly softened. You see, he just wanted me to be happy and to chase my dreams. His goal—for me to love softball as much as he loved baseball—wasn’t the most important thing. He just wanted me to follow my passion, whatever it was. And it was clear that my passion was soccer.

Pushing Moves You Forward

There’s probably someone really important in your life who pushes you toward a goal—it could be your teacher, your mom, your grandfather, or someone else entirely—and you might disagree with them sometimes. I disagreed with my dad all the time! But I think you still need to value their place in your life. If you listen to them and let them in, they will probably nudge you just a little harder to find your passion. I’ll always thank my dad for doing that for me.

CHAPTER 2

* * *

You probably have a soccer league in your town. Most places do, as soccer is, believe it or not, the third most played sport in America right now, behind basketball and baseball. Thirty percent of households in the United States have at least one member who plays the game. People began to pay attention to professional soccer in 1994, when the United States hosted the men’s World Cup, but for girls, 1999 will always be the year that women’s soccer exploded. That’s when the United States won the women’s World Cup. But more on that later. . . .

In Diamond Bar, soccer was a really big deal for kids. Every kid I knew played recreationally, and the AYSO—the American Youth Soccer Organization—had a few great leagues right around us. I loved soccer right away, and unlike with my sisters, who eventually gave up the sport, that never changed. We’d run around so much as kids that taking off down the field came naturally for me. I was really fast, and I loved to go for the ball. I was always kind of a tomboy, too. I didn’t dress like a boy, but I loved playing with the guys and beating them. For example, when we’d run for charity at my elementary school, I took so much joy in getting a better time than all the boys. That’s part of the reason I gravitated to soccer—I could play with boys just as easily as I could play with girls.

I started dreaming big about soccer when I was around eight. I just loved it. I counted the minutes till I was on the field, and I had a blast with my friends during practices and games. Plus, getting better and better at soccer gave me a goal to reach for. I wrote a letter to my mom when I was eight, and I’m so glad she kept it because it really says a lot about where my head was then.

My dad didn’t know a thing about the sport, though, and he didn’t really want anything to do with it in the beginning. He just didn’t understand why people liked it. Of course he supported me and my sisters, but he wasn’t involved in the beginning like he was with softball.

But he started to get serious when he began paying attention and better understanding the game. At age nine, I started practicing with him—not just doing drills and making shots but also running. He would have me practice with ankle weights for a few laps; then I would take off the weights and run like I was flying. I’m not sure if it helped at all with my speed, but it definitely helped with my endurance.

My dad also wanted so badly to nurture my natural ability that he took coaching lessons and bought one of those pop-up goals so that we could play in our yard. Pretty soon he wasn’t just coaching me on my own; he was heading up my AYSO teams. On the years he didn’t coach, he and my mom didn’t miss a single one of my games. And they even hired a speed coach for me when I was ten!

As my dad learned more about soccer, he got more interested in technique and he began to focus on my ability to finish. When we’d play in the yard, he’d stress again and again that making a shot is one thing but finishing is another. Finishing is actually getting the ball to go where you want in the goal, most often low and in the corners.

“Dad, I’m tired. I think we should just do finishing tomorrow,” I remember saying.

“But, Al, you gotta work hard every day if you want to be the best. Well, you are the best, but you can be better. Come on. We’ll get ice cream from 7-Eleven after.”

And that would work, every time.

Now that I think about it, finishing in soccer is a lot like following through with a goal in life. It’s one thing to try to make a goal, but it’s another to pursue a precise path toward that dream. Sometimes the path may not be clear, but when it is, you should go for it. I have no idea if my dad had made that connection at the time, but the lessons he taught me about finishing stick with me to this day.

• • •

During t

he summer of 1999, when I was ten years old, things really changed for me. That was the golden summer, when Mia Hamm, Julie Foudy, Kristine Lilly, Brandi Chastain, and the rest of the national soccer team exploded onto the international scene and captured the World Cup title. The team’s overtime win in the final against China ended weeks of some of the most dramatic play the world had ever seen. I’d watched so many games on TV, but that final was on a whole different level.

I especially loved Kristine Lilly—she was the kind of forward I wanted to be. She was fast and hardworking, and she could change a game instantly—her quiet energy was infectious. She wore #13, and I play in that number in her honor. I met her briefly at a youth national team camp when I was sixteen. She met with us in the locker room at the StubHub Center just to say hi and give a few words of inspiration. Honestly, I couldn’t even tell you what she said. But I remember the way she carried herself, so confident and comfortable in her own skin. She was so content with her life and her accomplishments, but she still wanted to meet me. I couldn’t believe it. That’s how I want to be with my fans.

But back to the 1999 World Cup. The final was being held in Pasadena at the Rose Bowl, which was so close to Diamond Bar. I didn’t get to go, so I was glued to the TV screen when the final began. There were ninety thousand people at the Rose Bowl—still the highest attendance any women’s sporting event has ever seen—and the excitement was so intense that I could practically feel it thirty miles away.

I watched every minute of that game, and when it went into a penalty shoot-out after remaining scoreless during all of regulation and two periods of extra time, I was breathless. When Brandi Chastain netted the final penalty kick, then fell to her knees and tore off her shirt in celebration, I screamed with joy.

Switching Goals

Switching Goals Tandem

Tandem Breakaway

Breakaway Hat Trick

Hat Trick Sabotage Season

Sabotage Season In the Zone

In the Zone Shaken Up

Shaken Up Under Pressure

Under Pressure Saving the Team

Saving the Team Win or Lose

Win or Lose Choosing Sides

Choosing Sides Settle the Score

Settle the Score